Paul Romer is Bad at Epidemiology

What happened and some research ethics

So I got into a fight the other day on Twitter. It wasn’t with a random account, but with pseudo-Nobel Laurette Paul Romer. Romer decided to take a break from his busy schedule being an economist to moonlight as an epidemiologist with this banger of a tweet:

I snarkily replied with “Normally when estimates have error bars this large you should quickly dismiss them and ignore the rest of the output of the modeling group that produced them” and we were off to the races. I stand behind my tweet; the error bars here are unusably large. For having the gall to question him and not shrink away when he replied, I am now blocked.

Let’s dig into why he is wrong and some philosophical disagreements on modeling.

Methodology issues

Romer, in the unlimited wisdom that is bestowed on you when you receive a Ph.D. in Economics from the Univerity of Chicago, made a giant methodological mistake. To come up with his numbers Romer took an early mortality prediction from the United Kingdom. With this prediction in hand, he multiplied it by the population ratio between the United Kingdom and the United States (1:5).

This is a fine back-of-the-napkin way of sketching out super-rough predictions, like a Fermi problem, but it is not robust. Romer made the fatal error of assuming that two separate populations would be affected by a disease in the same way and the only difference is the scale. It would be like saying that because Zimbabwe had 310,000 cases of Malaria in 2019, the United States should have about 6.8 million cases because it is 22 times larger. The US actually had about 2,000 cases none of which were acquired in the US because of malaria control practices in the 1950s.

The US and UK differ in several ways. The case facility rate has been dropping in the United Kingdom compared to the United States over the past year. Additionally, the UK is more vaccinated than the US and has a higher uptake of booster shots. On the other hand, the US is mostly vaccinated with Pfizer and Moderna while the UK is mostly AstraZeneca. New data shows that while AstraZeneca protects against severe illness and death after 6 months it might not provide much protection against the initial infection by the omicron variant. It is plausible that in a country with more AstraZeneca vaccinations, unvaccinated people would be exposed quicker than in a country with more Pfizer and Moderna.

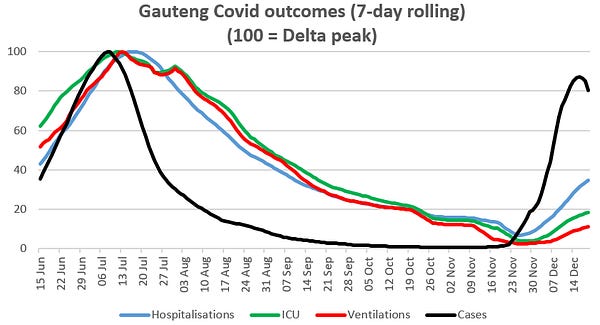

The original UK numbers were run a bit ago when details about omicron were far murkier than they are today. That isn’t to say that we have a firm idea of exactly what omicron is supposed to do, but we have new data coming out of Gauteng. This data shows a peak below that of the delta wave 6 months ago. I would be interested to know how much tighter the error bars get on those UK predictions with this additional data.

With all of this, you need to run slightly more sophisticated math than multiplying by the population ratio to come up with a peak number of deaths in the United States. There are too many changes in underlying possible explanatory covariates to just wave them away. You especially don’t dismiss people who question your numbers as not understanding uncertainty and shout about “that’s what the numbers say”.

About those error bars

The number that Romer came up with is 3,000 to 30,000 deaths per day. This is a massive range that is too big to make decisions off of. On one hand, 3,000 deaths per day is about the peak of the last big wave in the US. To combat it, you need to do much of what the US has done over the past 2 years. On the other hand, 30,000 deaths per day is unfathomably horrific. There are the same number of fatalities in motor vehicle crashes each year in the United States. I would have significant concerns that the social fabric of the US could not survive it. At 30,000 deaths per day (600,000 deaths per month), COVID becomes an epistemic threat to the future of humanity and the door opens to much more painful measures.

Faced with these numbers, what is a policymaker or citizen supposed to do? The kind of responses to the top-end scenario infringe on the civil liberties of citizens quite a bit to stop the spread. At the same time, elected officials would like to avoid being in office when mass graves are dug as a consequence of their decision. Worst case, policymakers become Buridan's Donkey between two bales of hay unable to make a decison so they choose to do nothing.

What are models for

George Box famously said, “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” With this in mind, I am a firm proponent that public-health models exist to be used to help make decisions. Models that are so uncertain of their outputs that a reasonable viewer can not interpret the results in a meaningful way should not get released. To me, this is a core part of research ethics.

In this case, we have a very high amount of uncertainty in a rapidly changing landscape. More data to refine a model was coming in by the day. Knowing that, modelers should resist the temptation to be first and hold off on releasing estimates until there is enough data to make reasonably certain estimates. The risk of causing excess deaths by overshooting and causing a backlash or undershooting and not suggesting a much lower number of fatalities is too high.